Terminal liver cancer patient ‘preparing for next life by doing good’

Roger Tan, 48, was diagnosed with incurable liver cancer in late 2024 and given less than 12 months to live. Despite this, he remains remarkably positive, focusing on meaningful work such as helping former inmates find purpose within society. The Straits Times/Asia News Network

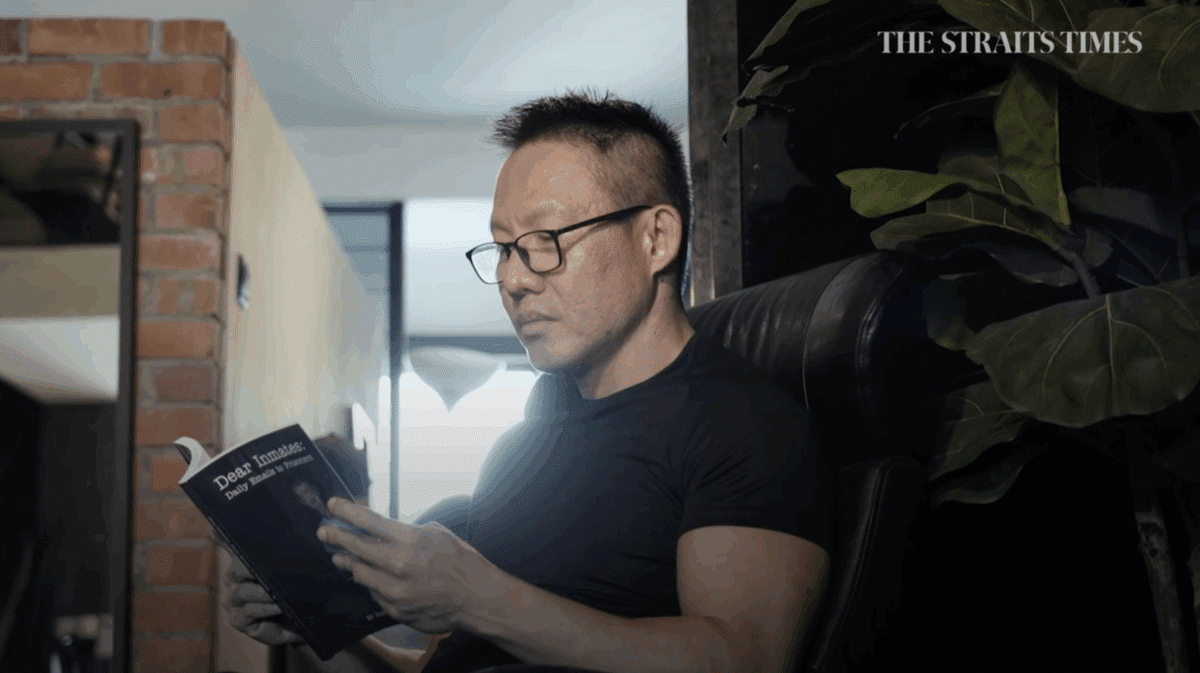

It’s hard to imagine that Mr Roger Tan’s days are numbered.

His fitted T-shirt hugs a gym-honed body, sleeves stretched over solid biceps, with no trace of middle-age spread. He is sharp, lively and quick on his feet.

But in December 2024, doctors told the 48-year-old, with the clinical certainty that only doctors possess, that he had just 12 months left. Liver cancer, they said. Terminal.

READ: A test of patience: A day in the life of a cancer patient in the Philippines

Yet, if you expect to find a man defeated, you are mistaken. A former risk manager with a global bank, his days are spent not in bitterness or regret, but in volunteer work and in writing.

Every day, he crafts an e-mail – sometimes about mindfulness, sometimes about self-compassion, sometimes just about the small joys of life – and sends it to a group of inmates he befriended during his years as a volunteer counsellor in prison.

Those daily messages were collected in his book, Dear Inmates: Daily Emails To Prisoners, which was launched in May. The book was published with the help of Ambulance Wish Singapore (AWS), the charity that grants last wishes to the terminally ill.

Chirpily, he says he is not scared of dying.

“I look back at what I’ve done in the past few years, and I’m very, very happy. It’s been meaningful, helping people. So, no regrets. Die, die lor.”

READ: Long lines, lengthy treatment wear out PH cancer patients

Mr Tan’s story began in a kampung in Lim Chu Kang, where his paternal grandfather owned a sprawling durian plantation.

As the youngest of three siblings, he grew up with space to roam, animals to keep, and a family that valued hard work and humility. His father was an engineer and his mother a factory worker who now works in a coffee shop, not for the money, but for the sense of purpose it gives her.

Outspoken and playful, he displayed his academic prowess in Ama Keng Primary and Bukit Panjang Government High schools, where he consistently ranked among the top in his cohort.

But entering junior college, he struggled to fit in among wealthier peers. Many of his schoolmates, he says, were rich.

“They went to Disneyland in primary school, played golf in secondary, and got cars when they got their licences. I felt out of place, and it made me ambitious. I told myself I needed paper qualifications to be like them,” he lets on sheepishly.

Fuelled by that ambition, he threw himself into his studies, chasing paper qualifications the way others chased dreams.

A degree in computer science from Goldsmiths, University of London, in 2001 was followed by a master’s in operational research from Nanyang Technological University, a master’s in finance from Imperial College London and, finally, a PhD in empathy media from the University of Hertfordshire, where his thesis involved creating a computer game to help people bond with their pets.

For four years from 2009, he worked for UBS in risk management. The bank not only backed his academic journey by funding his master’s in finance in London but also granted him a sabbatical to pursue his PhD. He was drawing a fat pay cheque but the sudden impact of a car accident in 2013 changed everything.

READ: Cancer burden: Draining people’s lives, pockets

He suffered a spinal injury that not only left him with chronic pain and spasms but also ended a long relationship.

“I was in a body cast for six months and when that was removed, a lot of things changed. My spine was crooked,” says Mr Tan, recalling how he even struggled to control his jaw and often drooled when speaking.

The accident was a wake-up call.

Portrait of Roger Tan, 48, who was diagnosed with incurable liver cancer in late 2024 and given less than 12 months to live, taken on June 4, 2025. He also distributed lunch with former inmates and volunteers to the elderly at THK Active Aging Centre at Cassia Crescent.

Mr Roger Tan, 48, was diagnosed with incurable liver cancer in late 2024 and given less than 12 months to live. ST PHOTO: CHONG JUN LIANG

On the recommendation of a friend, he turned to mindfulness and self-compassion to confront his bitterness, first through books and then through Buddhist philosophy.

“Buddha said, if you don’t have time, just learn compassion,” he says.

“I realised that underneath everything I was doing, my ultimate goal was happiness. I thought getting a high-paying job in a foreign bank would make me happy. But it was still just a job – it didn’t equate to happiness.”

The Buddhist principle that helping others brings happiness resonated deeply.

“I learnt that helping others makes you happy. I realised that if I couldn’t find people to help me, I could be the one to help others.”

That same year, Mr Tan left the bank to join a friend’s start-up – T.Ware – which builds intelligent wearables for health and wellness. One of their products is the T.Jacket, which delivers gentle decompression therapy designed to support children with autism.

He also started a small non-profit named H Project (H stands for hope) to do volunteer work. Among other things, he helped to set up a library and befriended patients at the Institute of Mental Health, and worked with the terminally ill at Dover Park Hospice.

Roger Tan, 48, speaking to the elderly after also distributing lunch with former inmates and volunteers to the elderly at THK Active Aging Centre at Cassia Crescent on June 4, 2025. He was diagnosed with incurable liver cancer in late 2024 and given less than 12 months to live.

Mr Roger Tan speaking to seniors after distributing lunch with former inmates and volunteers to the elderly at THK Active Ageing Centre in Cassia Crescent on June 4.ST PHOTO: CHONG JUN LIANG

Through a Buddhist charity, he started volunteering with the prison in 2018.

“The inmates are not as scary as you think,” he says. “Most of them are just everyday people who made mistakes. Many are there because of drugs, but some have mental health issues like ADHD, borderline personality disorder, autism.”

To better understand and help them, he enrolled in the Singapore University of Social Sciences (SUSS) for a degree in forensic psychology, diving into how psychological insights shape law enforcement, rehabilitation and crime prevention in Singapore.

“At first, I just went in to counsel inmates,” he says. “But I realised that sometimes, the topics weren’t clear-cut, so I started teaching them about self-compassion and mindfulness.”

When Covid-19 hit in 2020 and in-person visits were suspended, he found a new way to connect: daily e-mails to inmates, offering encouragement, life lessons, as well as news and a sense of connection to the outside world.

“One inmate told me his family wrote to him every day – father, mother, sister, wife, all taking turns,” he recalls. “He wished he could have me writing to him too.”

So Mr Tan started writing to him every day. It was not long before others asked if they could also receive e-mails from Mr Tan, and the mailing list grew.

“At its peak, I was e-mailing almost 100 people,” he says, adding that inmates get access to tablets to view their letters, postcards and greeting cards.

These e-letters are vetted by prison authorities who reject messages with vulgarities, scriptures or topics deemed sensitive. For instance, soccer news reports are not allowed in case they encourage gambling.

“I learnt as I went along,” says Mr Tan, whose initiative won him the Raise Award from SUSS in 2024. The award honours student projects that have made a significant impact on the community and beyond.

“Writing an e-mail each day is not a hard thing to do. Just think how many e-mails we write at work each day,” he says.

Mr Roger Tan with his mother and friends at his book launch in May.ST PHOTO: CHONG JUN LIANG

The notes of appreciation he receives convince him he is doing the right thing. One inmate – whose letter is reproduced in his book – writes: “Keep up your good work for inmates. Whenever an inmate changes their life, his or her tears of gratitude will shine like a star in heaven for you.”

Being diagnosed with cancer in August 2024 struck Mr Tan like a bolt from the blue.

“It was a routine check-up,” he says. “My family has a history of liver issues and hepatitis B, so I’ve been getting checked every year since I was 14.”

Doctors found something in his blood and a tumour in his liver. After undergoing an exhaustive battery of tests, including a CT scan and an MRI, he was told he had cancer.

An operation to remove the tumour went awry when it “exploded” during the procedure, leaving him with a blood mass in his liver.

Four months later, in December 2024, he was told he had 12 months to live.

“I now take a chemo tablet daily because my condition is such that there’s nothing else they can do,” he says calmly. “My problems now are from chemo, not the cancer. My throat gets very dry, and hurts. My eyes get very dry too.”

Despite the grim prognosis, he remains positive.

“I’m not convinced I have only a year,” he says. “I’ve read about people who outlive their prognosis by years. But even if it’s true, I’m not scared of dying.”

One of the first things he did after his diagnosis was to compile the e-mails to prisoners into a book, with the help of AWS. The book launch felt like a living funeral, he says. Friends came not only to congratulate him but also to wish him goodbye.

“A few of them cried, but it was okay. I think that’s something that happens. We just move on.”

Life goes on, he says. He is still studying forensic psychology at SUSS, hoping to go all the way to a master’s degree, if time allows.

“The course is stackable. I can stop any time, or keep going. But I want to keep learning, keep helping.”

Mr Tan is also focused on making sure that his work continues. He is grooming successors to take over the e-mail project and working with SUSS to formalize the Robin Hood Squad – a group of former inmates, their families and volunteers who do charity work together.

Besides doing charity, the aim is to help inmates reintegrate into society, he says.

The squad, now about 20 strong, packs care bags for orphans, sings for those with mental disabilities and serves food to hospice patients.

“I want to make it a legal entity, so it’s not just a friends’ thing,” he says. “I’m looking for someone to take over, so the work can continue after I’m gone.”

As for death, he says: “As a Buddhist, I believe in reincarnation. If I do good now, maybe I’ll have more resources to help people in my next life.” /dl